The Last Big Boys & Where To See Them

The last revenue train hauled by a Union Pacific Big Boy ended its run early in the morning on July 21, 1959. Most of the 25 Big Boys were stored operational until 1961 and four remained in operational condition at Green River, Wyoming until 1962.

Eventually their time in company revenue service came to an end with the last Big Boy officially retired in July 1962. At the time of their retirement, each of the first 20 Big Boys ordered had accumulated over 1,000,000 miles and each of the last 5 had traveled over 800,000 miles.

Seventeen of these steam giants were scrapped, but eight survive. Incredibly, one is operational. Union Pacific has restored #4014 and tours UP lines drawing huge crowds wherever the locomotive goes. For the #4014 restoration story, see our article “The Big Boy Miracle”. Doing the math, that still leaves seven Big Boys. Where are those survivors?

Where are the eight Big Boy survivors?

While #4014 is now in company public relations service, the other surviving Big Boy locomotives are displayed in museums, indoor and outdoor, all over the United States.

4004: Holliday Park, Cheyenne, WY

Big Boy 4004 is displayed in Holliday Park on US 30 in Cheyenne. It was placed there during the summer of 1963. According to Bess Arnold’s 2004 book, “Union Pacific: Saving a Big Boy and other railroad stories”, the 4004’s salvation is the direct result of a retirees group that recognized how quickly the railroad was disposing of its steam power.

The group reached out to UP Vice President-Operations E.H. Bailey about saving a Big Boy. The group then went to the Cheyenne mayor’s office, where they got approval to preserve an engine. The UP Old Timers Club sold raffle tickets and collected more than $2,000 to build a concrete pad for the locomotive in what was once Holliday Park’s Lake Minnehaha.

A diesel switcher moved the locomotive across 600 feet of panel track in June, 1963. As an extra precaution, a city truck followed to feed air to the locomotive’s brake system in case it broke free from the diesel, and a crawler tractor was tethered to the 4004 as a further safeguard to prevent it from rolling free. It was a worry because some smaller parts had been removed from the locomotive over the years to keep other steam engines active. But it was a safe moved and 4004 stood proudly in Holliday Park.

A 1986 rainstorm caused Holliday Park to flood so that water reached the top of 4004’s drivers. In 2005, 4004 received some cosmetic work including a new paint job, lettering and new windows which greatly improved the locomotive’s appearance.

Cheyenne is also the home of UP’s steam program. Located in the steam shops are several historic steam locomotives, several are stored such as Challenger 3985. Two are operational and used for Union Pacific public relations, UP’s “Living Legend” 4-8-4 #844, a Northern class and of course Big Boy #4014.

4005: Forney Transportation Museum, Denver

Union Pacific 4005 was the only Big Boy converted to burn oil. It was converted as an experiment in 1946, during a coal miner’s strike. The locomotive operated in this fashion through March 1948, but the test was deemed unsuccessful and the engine was reconfigured to burn coal, which it did for the rest of its operating life.

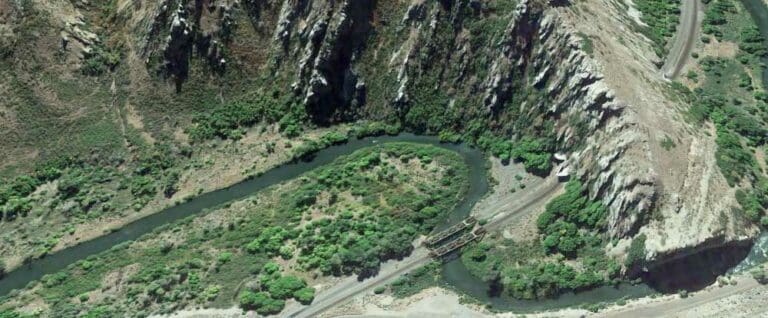

The locomotive was involved in a fatal derailment on April 27, 1953, on a run from Rawlins, Wyoming, to Green River, Wyoming. 4005 was pulling 62 cars and a caboose when it entered an open siding switch at Red Desert and derailed at 50 mph. The locomotive and tender came to rest on their left sides and the first 18 cars piled up in the crash, which killed the engineer, fireman, and head-end brakeman. 4005 was repaired at Cheyenne and returned to service, still bearing scars of the accident on the left side.

At the end of its career, 4005 had been partially dismantled in preparation for shipment to Argentina. However, the recipients in Argentina were unable to pay the shipping bill, so 4005 stayed in the US and was instead donated to the Forney Transportation Museum in Denver.

4005 was displayed outside at the Forney Museum for many years. In January 1999, it was temporarily moved next to the Platte River at 15th Street, it was moved again before making it back to the museum and this time inside to a protected resting place inside the building. During these moves, to prevent major damage to the cylinder bores, 4005’s main rods were removed.

A substantial amount of work was required to repair some critical damage to the trailing truck centering devices. When the engine was originally placed in the Forney Museum, a torch had been used to cut off parts of the casting that control the limits of lateral movement of the trailing truck. These had to be renewed in order for the engine to be able to negotiate curves during its moves.

The work has paid off and now, under cover and cosmetically restored, the 4005 is one of the better and more accessible examples of the Union Pacific Big Boy.

4006: National Museum of Transportation, St. Louis

In 1954, long before the 4-8-8-4s were withdrawn from service, negotiations to save a Big Boy began. Union Pacific formally donated Big Boy 4006 to the museum in June, 1961. To get to 4006 to St. Louis, Union Pacific moved it to Kansas City in a journey that took four days at a top speed of 25 mph. At Kansas City, Missouri Pacific took over for the rest of the trip.

Instead of going straight to the St. Louis museum, the locomotive went to the Alton & Southern shop in East St. Louis for cosmetic work that took about a year. During its delivery to the museum, the locomotive encountered one of the best-known steam locomotives in American history, the American-type “General” of Civil War “Great Locomotive Chase” fame.

The meeting took place when 4006 left the Alton & Southern yard in East St. Louis. With two diesels pulling, 4006 rolled across the MacArthur Bridge over the Mississippi River. The General was in St. Louis on the first leg of a Civil War centennial tour. “One hundred years of steam locomotive development were embraced in the encounter between the 600-ton articulated giant built in 1941 and the 31-ton 4-4-0 constructed in 1855”, said the Museum of Transportation.

4006 is on display outside but it kept up by the Museum. It was painted in 1995 and is displayed directly ahead of another Union Pacific behemoth, this time a diesel, Centennial 6944. Stairs provide access to the cab of 4006 where most controls are helpfully identified.

4012: Steamtown National Historic Site, Scranton, PA

In 1964, Big Boy 4012 was moved from the Union Pacific rail yard at Council Bluffs, Iowa, to Bellows Falls, Vermont, to become the largest and most impressive piece in Nelson Blount’s extensive private Steamtown U.S.A. collection.

The trip was not without excitement. First off, according to James R. Adair’s 1967 book, “The Man from Steamtown”, it cost Blount $6,000 just to ship the locomotive dead-in-tow. Then, the centipede tender derailed three wheels at Manchester, N.Y., causing much consternation among the crews who had to rerail the giant tender.

Nelson Blount’s Steamtown Museum in Vermont was a noble effort to save as many as 30 steam engines, including 4012, from the scrappers torch. The effort succeeded, but not without controversy and hardship. After Blount’s death, and without his perusal wealth, the museum rapidly declined as did the collection. In hopes of moving it to a larger metropolitan area, the whole museum was moved to Scranton, Pennsylvania in 1984, but soon went bankrupt.

In a controversial move, the Federal Government stepped in and bought the entire collection and the former Delaware, Lackawanna & Western rail yard in Scranton and established the Steamtown National Historic Site. 4012 had been displayed in the front of the Lackawanna Station Hotel in downtown Scranton for many years. In 1993, after bridges between the Hotel and Steamtown were replaced, 4012 was moved into the yard at Steamtown and is now one of the centerpieces of the multi-million dollar historic site.

Steamtown National Historic Site may have started in controversy but it is one of the premier rail museums in the country with a roundhouse and restoration facilities rivaling even Union Pacific’s steam shop in Cheyenne. And 4012, while displayed outside, is kept in tip-op condition. There is however, no plans to restore 4012 to operation.

4014: UP Steam Shops, Cheyenne, WY (or on tour!)

Cheyenne was not 4014 first post retirement home. Union Pacific 4014 was donated to the Southern California Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society in January, 1962 and put on display at the Los Angeles County Fairgrounds at Pomona. In 1990 the Big Boy had to be moved from one display area to another at the large fairgrounds complex, 4014 gave the movers quite a surprise.

During the move, 4014 moved so easily that it got away from them and ran into the tender of another steam locomotive in the collection, Santa Fe 3450, a 4-6-4 Hudson type. The moving crew left things that way over night while planning on repositioning it the next day. When they arrived the next morning they found 4014 had continued to creep forward overnight, pushing 3450 slowly off the end of the temporary track sections they used for the move. Neither locomotive was seriously damaged.

It was this “ease of rolling” after so many decades outside (but in the relatively dry Southern California weather) that attracted Union Pacific when they went looking for a Big Boy locomotive to restore. The company began planning for the upcoming150th anniversary, in 2019, of the joining of the nation, east to west, by the transcontinental railroad early on – in 2012. And decided an operational Big Boy would put an exclamation point on the “Golden Spike” celebration.

On July 23, 2013, Union Pacific announced that it had reacquired Big Boy 4014 from the Southern California chapter of the Railway and Locomotive Historical Society, with the goal of restoring it to service.

The amazing tale of how No. 4014 came to be the “chosen one” has to include the heroic efforts of members of the Southern California Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society. Chapter volunteers removed firebrick, cleaned out the ash and cinders from the smokebox and firebox, then needle-scaled both to remove rust and scale, cleaned and painted the gauges, repaired the firedoor, and rewired the engine for lights.

They also scooped out sand from the domes, made a sheet metal cover for the whistle well to keep rainwater from entering the smokebox, installed the pistons in the cylinders, and painted and lettered the engine. They kept the engine oiled and greased. They even set it up so that compressed air could power the bell and blow the whistle. All of this for maintenance of their display piece, with no knowledge that one day their Big Boy would be “the” Big Boy.

4017: National Railroad Museum, Green Bay, WI

Negotiations began in 1960 between the museum and Union Pacific Harold Fuller and UP leadership, and a deal was quickly struck for a donation. Now, how to get 4017, the chosen Big Boy, to Green Bay. Union Pacific was to deliver 4017 to the Chicago & North Western who would ferry the Big Boy all the way, but at the last moment, the Milwaukee Road stepped in and asked for the honor of moving the engine.

So, the Milwaukee Road (Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad) was given the job, but the Chicago & Northwestern still got a piece of the glory as the Milwaukee Road did not enter Green Bay. The Milwaukee Road had to hand 4017 over to the Chicago & North Western for final delivery.

Big Boy 4017 is in good to very good cosmetic shape. She was sand blasted and repainted in 1995. The firebox is electrically lighted and viewable by the public. While displayed outside for decades, in the summer of 2000 the museum began construction of a new “display hall” to provide shelter the 4017 (and other locomotives).

4017 was completely repainted in 2000 including a color match to reproduce the effect of the waste oil/graphite mix used to paint the Big Boy’s fire and smoke boxes during normal operation. By 2002 the new display facility was ready and 4017 was moved in. Visitors can enter both the cab and the tender.

4018: Museum of the American Railroad, Frisco, TX

Just prior to retirement was shopped in April 1957 at Cheyenne and ran the following September during the railroad’s annual grain rush. Being ‘back in service’ was short-lived however, and 4018 was stored at Green River again by October, never to run again. It has however moved a couple of times in its retirement.

Donated by the Union Pacific, the locomotive was sent to Dallas, Texas and the Age of Steam Museum at the Texas State Fair in 1964. Running out of space at the Dallas location, the museum moved to Frisco was renamed the Museum of the American Railroad. In August of 2013, Union Pacific 4018 went by BNSF rail, dead in a freight train, to the new location in Frisco.

4018 is displayed outside, available to the public. It was repainted in 2007. In 1998 there was some brief excitement – and hope – when it was announced that 4018 would be restored to operating condition for use in a movie titled “Big Boy”, but the movie never materialized. 4018 awaits her day in the movie lights.

4023: Lauritzen Gardens, Omaha, NE

Toward the end of their careers, both 4-6-6-4 Challenger 3985 and 4-8-8-4 Big Boy 4023 were given general overhauls so that they could continue to run for a few more years. In 1957, they were placed in storage in the Cheyenne roundhouse. 3985 and 4023 were kept inside the Cheyenne roundhouse until the mid-1970s, when 3985 was placed on display outside the Cheyenne depot and 4023 was relocated to Omaha and placed adjacent to the UP’s Omaha shops.

It was 1981 when a group of Union Pacific retirees asked for, and received permission to restore Challenger 3985. When the Omaha Shops closed in the late 1980s, 4023 was then moved to Omaha’s Kenefick Park where it sat on display for many years next to Union Pacific’s diesel giant, Centennial DDA40X 6900.

In the early 2010s, the city of Omaha decided to re-design the riverfront area including the old UP shops, local industries, and Kenefick park into a new convention center. 4023 was to be placed on display at the convention center site. However, a change in the convention center plans no longer included the display of 4023 and the DDA40X.

In anticipation of the convention center display, both locomotives had been temporarily moved to the Durham Western Heritage Museum in downtown Omaha. New plans were made to use the locomotives as a huge “welcome sign” to Omaha. In March of 2005, 4023 was moved to its current location at Kenefick Park in Lauritzen Gardens.

This move required a trip over city streets in a special cradle designed to spread the weight of the locomotive. Wasatch Railroad Contractors performed a complete cosmetic restoration of the steam locomotive in the five months following the move. In addition to a new jacket, many functional appliances were replaced with new, mock appliances. This included the safety valves, whistle, and lubricators. 4023 now gives anyone traveling I-80 through Omaha a real eyeful. And, the public can visit both locomotives.

Epilogue, “Never say never?”

As we can see by the surprise announcement in 2012 and the subsequent Union Pacific Big Boy 4014 tours, the Big Boy story is never really over – because the nation’s love for steam and for the Big Boy in specific, in not over. But what could be next? It is just not safe to speculate. 🙂 It’s easier to say what we know can not happen.

There are no more Big Boy locomotives to be “pulled out of a dusty old roundhouse” somewhere. Other than the eight survivors, the rest of the 25 total Big Boys have been scrapped. So, the universe of Big Boy steam locomotives is finite. Most of the survivors are in no shape at all to be restored to operating condition. It’s a combination of the million miles they retired with and so many of them spending so many years (over 60 now) outside in all kinds of weather.

There are a couple that could be candidates for restoration into operating condition. 4005, which has spent the last few years inside at the Forney Museum in Denver could be a candidate. Number 4018 has been in the drier climate of Texas and most specifically 4012 which is owned by the Federal Government and resides at Steamtown in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Realistically however, only two places in the United States, and possibly the world, have the expertise, the tools and the funding for such a big “Big Boy” job. The Union Pacific Steam Shop in Cheyenne and Steamtown’s roundhouse steam shop. Union Pacific, a private, for-profit company, ahs already devoted massive resources, and continues to do so, to bring 4014 back to life. The Federal Governments may be the only operation left with the wherewithal to do the job – and Steamtown maintains there is no interest at all in restoring 4012 to operating condition.

Never say never? Famously, the narrator of the best video documentary on the Big Boy, the Pentrex show “Union Pacific Big Boy Collection”, at the end of that show said an operating Big Boy locomotive would never happen. And here we are, with Union Pacific Big Boy 4014 shining the rails once again. But rather than speculate, we can certainly enjoy the eight that do survive, and the one Big Boy to come back from the dead and pull a train again.

Railfan and model railroader. Writer and consumer of railroad news and information.