Allegheny or Big Boy, Which is the Largest Locomotive?

Allegheny or Big Boy Both Union Pacific and Chesapeake & Ohio heavily promoted their steam flagships, the Big Boy (4-8-8-4) and the Allegheny (2-6-6-6) respectively, as being the largest, most impressive steam locomotives ever built. Both locomotives have their fans who claim the superiority of their favorites. And strictly by the numbers, there is no clear “winner”.

Before joining one side or the other, let’s take a closer look at the two steam giants, in order of their appearance on the railroad stage. Checking notes… both machines were built in 1941. Let’s try the alphabetical approach then.

The Allegheny

Built by the Lima Locomotive Works, the 2-6-6-6 class was an articulated locomotive, with two leading wheels, two sets of six driving wheels and six trailing wheels. Two classes of 2-6-6-6 were built and one of them was the Allegheny. The locomotive was designed to haul heavy trains over the steep grades of the Allegheny Mountains, especially the route between Hinton, West Virginia and Clifton Forge, Virginia, hence the name.

The Grade

This Hinton – Clifton Forge route included a 13 mile .577% grade to the 2,072 foot summit of Allegheny Mountain and then a descent down a 1.14% grade to Clifton Forge. Both steep grades to be conquered, at speed, if the railroad wanted to remain competitive.

Locomotives built in the 1920s and early ‘30s were getting old, and just as importantly were quickly being made obsolete by new steam technology. The Lima Locomotive Works, one the nation’s preeminent builders of steam, and on the cutting edge of steam technology, approached the Chesapeake & Ohio with a new more powerful engine design: a six-coupled, single-expansion articulated locomotive, with a big firebox and a very large boiler.

The Design

The large fire box was placed behind the drivers and required an unusual six-wheel trailing truck to support it. This gave the design a wheel arrangement of 2-6-6-6. The Allegheny boiler was capable of delivering 7,500 horse-power. This was far greater than any other reciprocating steam locomotive could develop.

To support this new power, and the fuel required, the tenders for these new locomotives were of the largest type used on the Chesapeake & Ohio, with a 25,000 gallon water tank and a 25 ton coal bunker. In order to keep the overall length of the locomotive and tender within the limit that existing turntables could handle, it was necessary to make the rear section of the tender higher, thus causing more weight to be at the rear than the front. The tender had a six-wheel leading truck, but an eight-wheel trailing truck was needed to carry the weight in the rear.

The Delivery

The first 2-6-6-6 locomotives were delivered by Lima in December 1941. They were designated Class H-8 and assigned road numbers 1600 through 1609. Each Allegheny was an investment of about $270,000. That would be over 5,000,000 today. A total number of 60 Alleghenies were built for Chesapeake & Ohio between 1941 and 1948.

Primarily designed for freight service twenty three of the Alleghenies were equipped with steam heat and signal lines for passenger service. However, the steam giants were were used sparingly in passenger service, pulling an occasional heavy mail train or a troop train during World War II. They were able to achieve a very impressive record even though passenger trains didn’t fit perfectly with their design.

Freight was to be the Allegheny’s specialty. Freight would be where the Allegheny would shine. The locomotive was designed to haul 5,000 tons of freight at 45 mph and to take that same train over the Allegheny Mountains with or without helpers – depending on how fast you need that freight. But the H-8 class would not be able to “shine”.

Final Thoughts on Allegheny

While the Allegheny 2-6-6-6 is considered by many to be the ultimate expression of the Lima Locomotive Works Super-Power Concept, they never got to use that power.

The Chesapeake & Ohio ended up using the H-8s primarily in “coal drag” service where they were unable to realize their full potential as high speed, high tonnage locomotives. While designed to haul 5,000 tons at 45mph, they were put to work hauling trains of 10,000 or more tons at 15 mph. Hidden away in the hollars of Virginia and West Virginia doing the important but unglamorous work of hauling coal, the Allegheny would not rival the Big Boy in the public’s mind.

The Alleghenies were retired beginning in 1952, with a last call for service in 1956.

There are two known Allegheny locomotives on display out of the 60 built!

The Big Boy

The Grade

Similar to the Allegheny, the Union Pacific 4000 class locomotives were purpose-built to conquer one particular section of railroad. The Union Pacific had to station helpers and crews to get trains over the Wasatch Mountains between Ogden, Utah and Green River, Wyoming. Often it took as many as three engines to get a train up and over that route. Starting in the mid-1930’s the Union Pacific began to design locomotives that could, they hoped, take a train over the 1.14% grade, unassisted, without helpers.

Two versions of this hoped-for locomotive were designed by the UP and then built by the American Locomotive Company (ALCo) in Schenectady, New York. The first design was a 4-6-6-4 locomotive, designated the Challenger class. It was a big leap in power, but in practice still could not manage that 1.14% Wasatch Grade without a helper engine. Almost, but not quite.

The Design

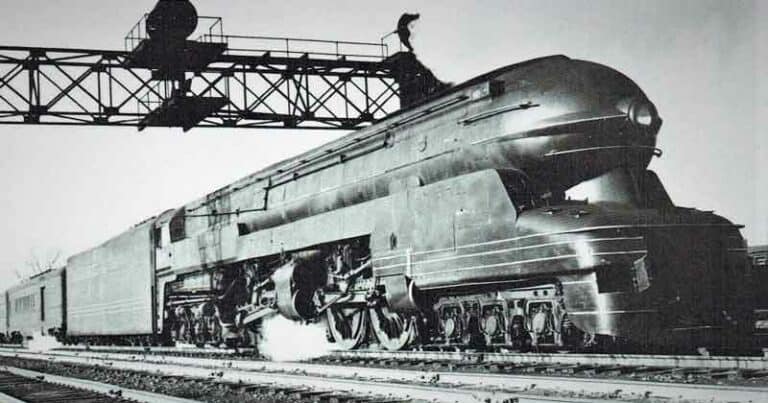

So, Union Pacific went back to the drawing board. If the Challenger was almost enough power, all they needed to do waas super-size it, right? And so that is what they did, designing a 4-8-8-4 locomotive and sending those plans to ALCo. The first of the series, number 4000 was delivered in September of 1941.

Dubbed the “Big Boy”, this locomotive was larger and heavier than its predecessor, the 4-6-6-4 Union Pacific’s Challenger, but it was closely based on it. The engine was built to run at speeds up to 80 mph, although they would never operate at that speed. The overdesign was done to ensure that the rotating parts would not be damaged while operating, and its highest speed reported during a test was 72 mph.

There were only 25 Big Boys ever built, but they have an incredible story.

The Union Pacific 4000 class was the only locomotive in the United States that used the 4-8-8-4 wheel arrangement. A four-wheel leading truck was at the front of the engine, followed by eight drive wheels, with a single piston driving a set of four wheels on each side of the engine.

Another set of eight drive wheels followed with a four-wheel trailing truck under the cab. The leading truck and first eight drive wheels were attached to a separate frame. Likewise the second set of drive wheels and trailing truck.

Between the two sets of drive wheels was a tongue and groove pivot point that allowed the front frame to articulate independently of the rear frame. The boiler, firebox, and cab was mounted to the rear frame. This made the locomotive more flexible. It’s called an articulated design.

The Delivery

Starting in 1941, 20, numbered 4000-4019, of the 4-8-8-4 first class engines were delivered. Union Pacific received authority from the War Production Board to build five more Big Boys in 1944; they were numbered 4020-4024. They were identical to the other locomotives except for the use of heavier metals in the boilers and rods.

Unlike Chesapeake & Ohio who chose to constrain the overall length of the locomotive and tender within the limit of existing turntables, Union Pacific decided to install new 135-foot turntables at servicing points. They also made changes to the track between Ogden and Green River and curves were adjusted to maintain a constant curvature. Heavier rail had been laid in many places and bridges had to be rebuilt to handle this new steam giant. The Big Boy was the largest engine that could operate on an existing standard gauge railroad.

Allegheny or Big Boy, The Winner is…?

The last revenue train hauled by a Big Boy ended its run early in the morning on July 21, 1959. Most were stored operational until 1961 and four remained in operational condition at Green River, Wyoming until 1962. The last Big Boy was retired in July 1962. At the time of their retirement, each of the first class Big Boys had accumulated over 1,000,000 miles and each of the second class of engines had traveled over 800,000 miles.

Is there a winner then? Between the Allegheny or Big Boy? One of them must be better than the other, since they are not identical. It’s not an easy call.

The two steam giants never competed head-to-head or even in the same type of service. While each locomotive had its strong points and weak ones, they were both great machines, and for sure they were both very impressive. Big Boy was larger, longer, and had a greater tractive effort, while Allegheny had greater horse-power. The H-8 has a larger fire box and a bigger boiler, though the Big Boy’s boiler developed a higher pressure.

Maybe we should pay more attention to the things they have had in common. Both steam giants were born in 1941; both were designed to handle specific heavy grades on particular routes. Both did their best, pulled millions of tons of freight, contributed to a winning war effort and both were honorably discharged when a more efficient, if less lovely, breed of iron horse – the diesel – came to claim the territory.

Railfan and model railroader. Writer and consumer of railroad news and information.