The Union Pacific Big Boy Story, 25 Massive Locomotives

The Union Pacific Big Boy steam locomotive was introduced at a fantastic time. In 1940, America was enjoying a period of growth following the Great Depression. It had been a slow recovery but consumers were buying more and factories needed more raw materials. Railroads were seeing more traffic and were looking for motive power to haul the traffic. For many railroads, it has been several years since they could afford to invest in new equipment.

And war was on the horizon. The United States was not yet the “Arsenal of Democracy” that she would become in a few short years; but country refused to allow Britain to face Hitler without the tools of war that were needed. Production of weapons and war vehicles had ramped up, and trains were needed to transport all of that.

The Union Pacific’s mainline connected East to West. From along the first transcontinental line, completed originally in 1869, the Union hauled freight and passengers from Omaha, connecting to the great rail clearing yards of Chicago through the Chicago Northwestern, to the large industrial centers of the west. The resurgence of the economy meant a lot of freight traffic.

The Mountains and the Hill

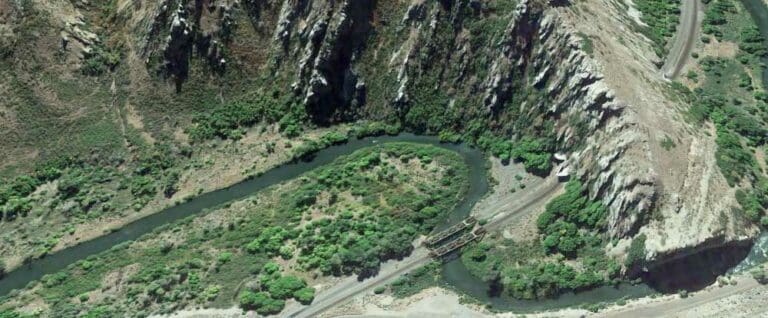

Being in a period of expansion, Union Pacific became interested in a new locomotive that could pull longer and heavier trains over the Wasatch Mountains in Wyoming and Utah and Sherman Hill between Cheyenne and Laramie in Wyoming without needing assistance from costly additional locomotives known as helpers.

It may be called a “hill”, but Sherman Hill is the crossing of the continental divide. The Union Pacific actually tunnels under the gentle peak, but the tracks crest at 8015 feet above sea level. The two tracks used in the 1940s, and still in use today with a third track added in the 1950s, are about a 1.5% grade. That’s nothing for cars, but it’s a good stiff grade for locomotives on a mainline with hundreds of freight cars in tow.

After Sherman Hill, heading west, the UP mainline had to traverse the Wasatch mountains between Green River, Wyoming and Ogden, Utah. The grade there is variable with a ruling grade of 1.14% upgrade (higher downgrade). Previously, the Union Pacific needed the power from multiple locomotives to traverse this section.

The Design and Delivery

William Jeffers was the president of the Union Pacific during this time and Otto Jabelmann served as the head of Union Pacific’s Research and Mechanical Standards Department. It was Jeffers who ordered Jabelmann to design and build a new engine capable of pulling – unassisted – trains over Sherman Hill and the Wasatch mountains.

The Union Pacific had a history of going its own way in designing large steam locomotives. The immediate predecessor to this locomotive was the Challenger series, a 4-6-6-4 behemoth. And they had rostered 88 of the famous 9000 Class, a 4-12-2 monster of pulling power. But this new series, initially to be named the 4000 Class, would be the pinnacle of big power for the UP.

Jabelmann’s designers and engineers concluded that the locomotive would have to have 135,000 pounds of tractive effort and an adhesion factor of four and to meet the demands. Designers decided it would require double-eight-driver wheels, articulated, for a total of 16 driving wheels with four lead and four trailing trucks, also known as a 4-8-8-4 in the Whyte Notation system.

Within three months, Union Pacific’s Department of Research and Mechanical Standards designed the giant locomotive and the American Locomotive Company (ALCo) of Schenectady, New York agreed to build the new Class. In an amazing feat of engineering and manufacturing, it only took about a year to complete the entire project, six months to design and fabricate the engine parts and another six months to deliver the first locomotive. On September 4th, 1941, number 4000 was delivered to the UP.

Railfan Depot has several DVD programs on the different Big Boys, including #4014 Returns to Steam.

Number 4000, not yet under its own power, was shipped from Schenectady, New York, via the Delaware & Hudson, New York Central, and Chicago & North Western to Council Bluffs, Iowa. After an inspection in Council Bluffs, #4000 traveled light to Omaha to pick up a train. It made several stops for water, fuel and crew, arriving in Cheyenne early the following day.

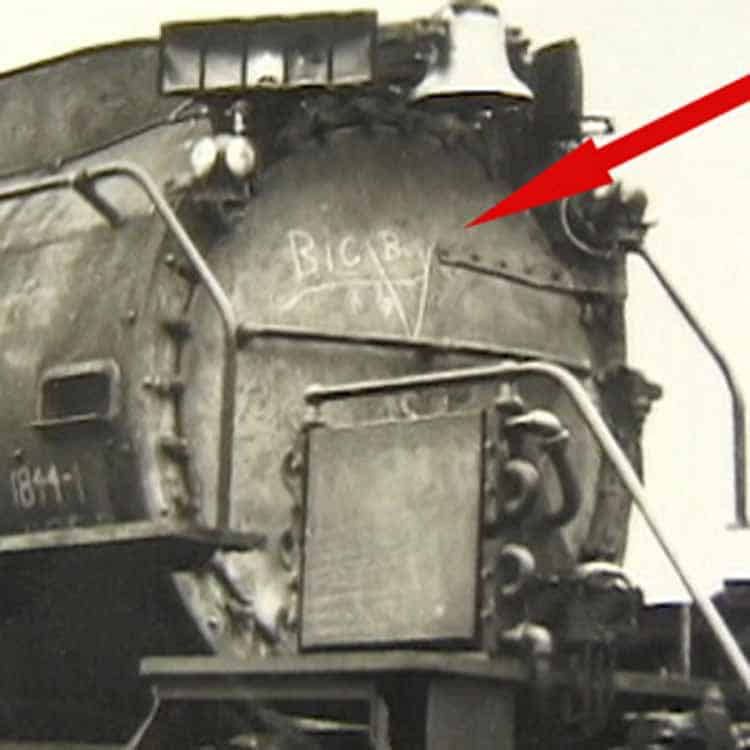

Naming the Big Boy

How did we get this far into the story without talking about how the “Big Boy” got its name? Well, it was during construction. The series was originally dubbed “Wasatch” by management, but at the ALCo plant in Schenectady, New York, an unknown workman chalked “Big Boy” on the boiler front and a picture was snapped – the rest is history.

Union Pacific had the Big Boy. C&O had the Allegheny.

Two versions of the locomotive were built in Schenectady. Starting in 1941, 20 of the 4-8-8-4 4000 class engines were made and numbered 4000 to 4019. Then in 1944, as the nation’s World War II effort demanded, Union Pacific received authority from the War Production Board to build five more Big Boys, numbered 4020-4024. They were identical to the first group with the exception that the boilers and rods were made heavier and more durable.

The Big Boy was built to run at speeds up to 80 mph, although they would not operate at that speed in usual practice. The overdesign was done to ensure that the rotating parts would not be damaged while operating. The highest speed reported during a test was 72 mph.

Bring Change

The Big Boys demanded changes to the physical plant, with some track changes made between Green River and Ogden to make some curves a bit more gentle. Heavier rail had to be installed in places and new 135-foot turntables had to be installed at the roundhouse servicing points at Green River and Ogden.

The 20 Big Boys that Union Pacific initially ordered from ALCo were at a cost of $265,174 each, while the final five cost $319,600. The equivalent cost for each engine would be over $6,000,000 in today’s dollars. The cost would not deter the Union Pacific as they had an increasing amount of freight to haul.

As soon as they could be delivered, all Big Boy locomotives were pressed into service. During World War II, the Big Boys spent most of their time moving freight between Green River and Ogden. After World War II, Big Boys were occasionally used for trips to southern Utah and began semi-regular service over Sherman Hill, going as far as Cheyenne, 483 miles from Ogden. The locomotives were a mainstay of service, until the diesel took over. And were some of the last steam locomotives in operation on the nation’s mainlines.

The last revenue train hauled by a Big Boy ended its run early in the morning on July 21, 1959. Most were stored operational until 1961 and four remained in operational condition at Green River, Wyoming until 1962. The last Big Boy was retired in July 1962. At the time of their retirement, each of the first 20 Big Boys ordered had accumulated over 1,000,000 miles and each of the last five engines had traveled over 800,000 miles.

The Survivors and the Most Famous Survivor

Of the 25 Big Boys, 17 engines were scrapped and 8 have been preserved, all which are currently on static display in various museums throughout America: 2 of the engines are displayed indoors after lengthy outdoor displays. Only 3 of the locomotives are displayed along original historic Union Pacific lines; they are located at Cheyenne, Wyoming, Denver, Colorado, and Omaha, Nebraska. Two Big Boys are now located on Union Pacific lines, in Dallas and St. Louis, after Union Pacific Mergers of the last 40 years enlarged the system.

Big Boy number 4014, the most famous of the Big Boy locomotives, the Big Boy once displayed at the Pomona, California fairgrounds, has been restored to operating condition. Big Boy 4014 was rescued from the Pomona Fairplex in 2013 and shipped by hospital train to the Union Pacific’s steam shop in Cheyenne, Wyoming in 2014.

Five years later, in 2019, Big Boy 4014, left the steam ships under her own power – for the first time in 60 years. 4014 toured much of the western USA to huge crowds, and the delight of many. The Covid-19 pandemic forced the cancellation of a planned 2020 tour, but the 2021 tour went off without a hitch! (You can see our coverage in the article “4014 in 2021”).

Railfan and model railroader. Writer and consumer of railroad news and information.