The History of Baldwin Locomotive Works

One of the most successful manufacturers of steam locomotives was Baldwin Locomotive Works (BLW). From 1825 to 1951, BLW produced over 70,000 locomotives and, although they struggled with the transition from steam power to diesel locomotives, they were the world’s largest producer of steam engines for decades. The history of steam-powered locomotives cannot be told without the inclusion of Baldwin Locomotive Works.

Matthias Baldwin, the company’s founder, began his career as a jeweler and whitesmith. In 1825, Baldwin partnered with machinist David Mason to manufacture bookbinders’ tools and devices for calico printing. These activities led to Baldwin designing and constructing a small stationary engine for his use. He soon gained a reputation for quality and efficiency in his engines and was solicited by others to build engines for other purposes. This led to an increased interest in steam as a power source.

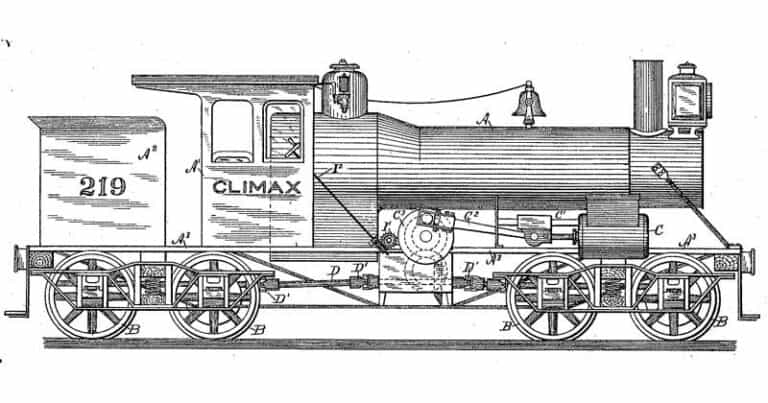

After building a miniature locomotive for an exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum, and having the privilege to inspect a yet-to-be-assembled locomotive that can from England and was awaiting service in New Jersey, Baldwin began his own quest of building a full-sized, steam-powered locomotive.

This first complete locomotive, called Old Ironsides, was completed in November of 1832 and was put into service for the Philadelphia, Germantown, and Norristown Railroad, where it served for over two decades. The wheels were made of heavy cast iron hubs but had wooden spokes and rims, which were standard at the time. Its 30-inch boiler required 20 minutes to generate steam and it could reach a top speed of 28 miles per hour.

Even as BLW’s reputation and production grew, the company struggled to survive the economic Panic of 1837. Baldwin brought in two new investors to help dig out of the debt that resulted from this difficult time. George Vail and George Hufty were with the company for a short time but were integral in helping DLW survive.

During the boom time for steam locomotives in the mid-19th century, Baldwin experienced both a renewed demand for their products and significantly more competition. Another economic panic in 1857 set the company back again. And while the American Civil War was initially a concern for the company – given their larger dependence on business with Southern railways – the company soon replaced the business from seceding states with purchases by the Pennsylvania Railroad and the U.S. Military.

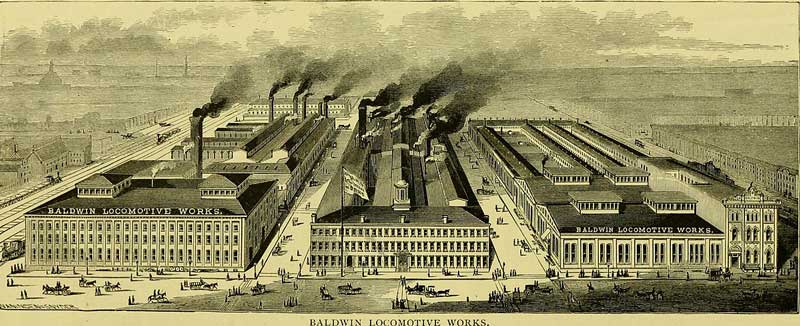

The death of Matthias Baldwin in 1866 came at a time when BLW was vying for the nation’s top locomotive manufacturer with Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works. The company continued to grow and in the 1870s was solidly in first place. They began to shift some of their production from the cramped space in Philadelphia to nearby Eddystone, Penn., where there were over 600 acres available for manufacturing.

The transition to this larger space was happening at a pivotal time in steam-powered transportation. During what many call, The Gilded Age, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the demand for steam locomotive engines in the United States was high. As it expanded its facilities, BLW also dealt with the challenges of increasing labor tensions and ongoing competition.

The Hepburn Act of 1906 created additional headaches for the locomotive manufacturing industry. This granted the government greater authority over railroad companies and led to limitations on how railroad rates could be set. This, in turn, depreciated the value of railroad securities, which caused many railway companies to reconsider orders for newer equipment. The ripple effects on the locomotive manufacturing industry were immediate.

Output for Baldwin locomotives dropped by 77% between 1906 and 1908, which also meant a huge reduction in their workforce. This was also a time of great labor movements in the Philadelphia area. Management was also dealing with finding and keeping a labor force that was increasingly interested in unionization. The death of William Henszey, one of the company’s partners, left a debt that required the company to incorporate in an attempt to raise $10 million in investments through the sale of bonds.

While Baldwin Locomotive Works remained a corporate contributor to the country through their manufacturing support of the military in WWI, the struggle to regain their once prolific spot in locomotive production never returned. During the war, the expanded facility in Eddystone was converted to manufacture rifles and artillery shells.

By the war’s end, their return to locomotive manufacturing was a significant part of the post-war rebuilding across the globe. Many European nations needed new locomotives to replace those that were worn out or destroyed during the war, and many manufacturers in Europe were not in a position to produce the replacements needed. As one example, from 1919 to 1920, Baldwin produced and shipped 50 4-6-0 locomotive engines that became a part of the Palestine Military Railway.

The post-WWI boom was short-lived. As the Great Depression enveloped the country, steam power was also losing its grip as the predominant method of propelling locomotives. Diesel engines were gaining a foothold in the market. Beginning in 1904, Baldwin Locomotive Works participated in the Baldwin-Westinghouse consortium as a means to research and study electric locomotives. Their early electric road locomotives were unreliable, expensive to operate, and did not serve for long.

Because many of the consortium’s efforts to develop diesel-electric power were unsuccessful, Baldwin Locomotive Works began to doubt the viability of diesel as a replacement for steam power. Many historians believe that Baldwin’s heavy investments in their Eddystone facility may have clouded their judgment regarding the future of locomotive propulsion, which contributed to their financial difficulties for their remaining years.

Samuel Vauclain, Baldwin’s Chairman of the Board, said in a 1930 speech that he believed the “advances in steam technology would ensure the dominance of the steam engine until at least 1980”. A notion that might seem quaint with the benefit of historic hindsight provides great insight into the eventual demise of Baldwin Locomotive Works. One of the contributors to this misguided thought process was the coal industry itself, which was hesitant to embrace a means of transporting their product that did not rely on their product.

As Baldwin kept its company’s position more solidly in the steam power realm, other competitors were carving away at their market share with more products powered by diesel. In 1938, a change in management brought about a renewed interest in developing diesel power. With other competitors already ahead of them, it may have been too little too late. In 1939, Baldwin had its first foray into manufacturing diesel locomotives, but they were designed for service in the rail yard, putting them far behind competitors who were already building diesel locomotives for hauling freight and passengers.

Fatefully, Baldwin Locomotive Works went all-in on the development of new steam-powered passenger service with the Pennsylvania Railroad at the end of the decade. Their duplex-drive S1 locomotive, and its next revision, the T1, were unsuccessful. After investing half a decade in these designs, they were unable to produce a single useful design. Their focus on steam power left them on the outside of the burgeoning diesel-powered transportation market.

By 1948, demand in the U.S. for steam locomotives had declined to just two percent. Just one year later, that number would be zero. Their inability to diversify their power methods and the failure of the few diesel products they did offer spelled the beginning of the end. Baldwin merged with former competitors to form Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton, but this did little to improve their market share in locomotive manufacturing.

By 1956, BLW had closed most of its facilities in Eddystone and was no longer producing locomotives. By the end of their 125 years of continuous production, they had produced more than 70,000 locomotives.

Many Baldwin steam locomotives are still in operation around the world. The steam-powered locomotives in Walt Disney World, which transport visitors around the Magic Kingdom in Orlando, Florida, are four Baldwin locomotives. They include:

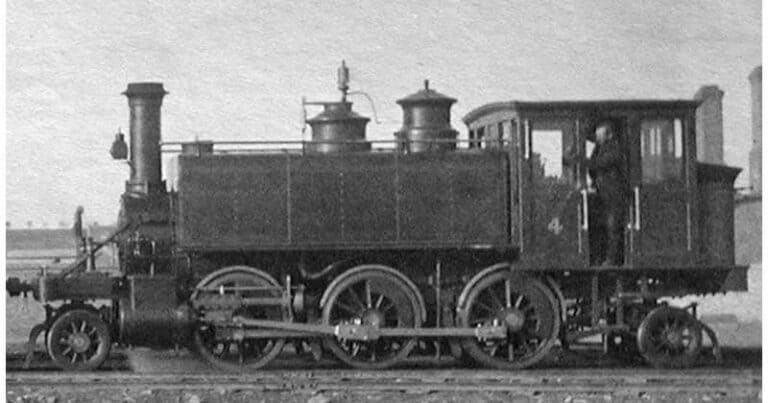

- The Roy O. Disney, a 1916 Class 8-C, 4-4-0, No. 4

- The Walter E. Disney & The Roger E. Broggie, 1925 Class 10-D, 4-6-0, No. 1 and No. 3

- The Lilly Belle, 1928 Class, 8-D, 2-6-0, No. 2

The story of Baldwin Locomotive Works is one of American ingenuity and hard work, while also being a cautionary tale about the speed with which businesses must change, adapt, and maintain their competitive edge. The development of our domestic rail system mirrors our growth as a country, and none of this would have been possible without men like Matthias Baldwin.

Matthia Baldwin’s original engine, which was used for many years, is currently on display at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

A longtime railfan, Bob enjoys the research that goes into his articles. He is knowledgeable on many railroad topics and enjoys learning about new topics. You can get a hold of Bob at his email link below.